Selling pay-per-views in 2024 is one of the greatest challenges facing boxing and MMA promoters. Even with a perfectly promoted event, there are so many entertainment options at our fingertips that sometimes fight fans will pass a quality fight card for something else.

Piracy is a massive issue and has gotten easier for viewers to do over the years. Back in the day, it was the equivalent of hot-wiring a car to steal the pay-per-view signal. Now, it's more like hopping in and driving off if someone leaves the key inside.

Pay-per-view sales are down dramatically from the last several years, and other than greater competition, one of the big reasons is that stealing of the signal is out of control. Unless a new technology is invented to prevent this, it has the possibility of being a death knell for those promoters and fighters who rely on pay-per-view revenue.

It's always been a problem, but it has spiraled out of control recently.

Why people feel it's OK to steal is beyond me, but that's the reality. You are taking a product someone is selling and investing their own money in and stealing it. There are a lot of fans who give promoters a hard time for what they pay fighters, but those same fans quite literally steal pay-per-view money out of those fighters' pockets and think nothing of it.

Even the argument that the pay-per-view prices are too high, which is very often legitimate, doesn't hold water. If you need a car and think a Mercedes-Benz is too expensive, you don't steal it; you buy a less expensive vehicle. But many fight fans think it's a victimless crime when they swipe the PPV signal when it's very much the opposite.

There are a lot of good things going on in boxing now, and some of the best are now starting to fight each other more regularly than they did before. There are a number of reasons for that, not the least of which has been the influx of money into the sport from Saudi Arabia.

A lot of promoters see the Saudis as an endless pit of money and are doing everything in their power to get a bit of it. Sooner or later, though, the Saudis are going to recognize that they're vastly overpaying for a lot of the fights they're buying, and the market will correct itself.

The Crawford-Madrimov card in Los Angeles last week, the first Riyadh Season event put on by the Saudis in the U.S., likely lost more than $10 million, several sources told KevinIole.com. The pay-per-view sales were negligible.

That show had its own set of issues, but there is little doubt that signal theft was significant. And that leads us to the second issue plaguing boxing promoters trying to push a PPV card:

The public relations efforts surrounding boxing are abysmal; beyond abysmal.

In the last five years, three long-time publicists were inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Top Rank's Lee Samuels was inducted in 2019. Bill Caplan, a popular Southern California-based publicist who was closely tied to former heavyweight champion George Foreman, was inducted in 2022. And Fred Sternburg, in my mind the greatest publicist in the sport's history, went in in June.

With the possible exception of Kelly Swanson, it's going to be a long time before any other publicist is even considered, let alone makes it.

It's in a fighter's interest who is getting points from pay-per-view sales to be made available as much as possible, but many of today's boxing publicists take the opposite approach. Just doing a series of interviews isn't going to guarantee a successful pay-per-view; it's far more complex than that. But not creating the awareness that a slew of media work does for a fighter will almost guarantee a show dies on the vine.

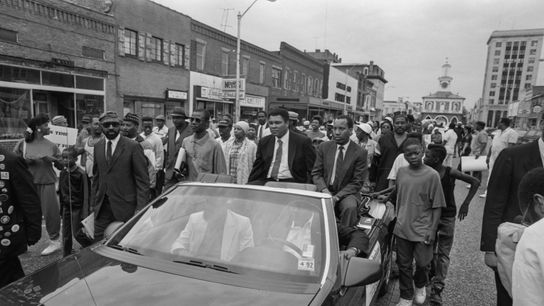

There wasn't pay-per-view in Muhammad Ali's day, but he was perhaps the most accessible athlete of all-time and, as a result, one of the most notable. The reason why he became so huge and one of the most recognizable figures on Earth is because he put himself out there. He talked to everyone. He appeared on all the many talk shows. He did sit-downs with newspaper writers and television sports directors. His workouts were open to the public and he'd frequently take questions when they were over not only from the media but from the public who showed up to watch.

Now, if a journalist writes or says something a publicist or promoter doesn't like, they're denied often access to an event that desperately needs all the attention it can get.

I get that it's difficult for fighters to do interview after interview after interview after interview. They get asked the same questions repeatedly and there are times the person interviewing them has never seen them fight. But they have short careers and if they want to earn millions and help grow their purses and the sport for future generations, that's a price they have to pay. Too many of them, and their publicists, fail to see that.

Think of how Ali was bashed in his day, but he never cut himself off and answered every question until no more remained.

Today's top stars are infinitely less accessible than those of the past, and it has a direct correlation to the declining PPV sales and general plunge in the popularity of boxing. With more competition, you have to promote more and smarter and not back off.

Too many of today's publicists see their jobs as protecting the fighters instead of building up their images and their notoriety.

His Excellency, Turki Alalshikh, the chairman of Saudi Arabia's General Entertainment Authority, isn't going to single-handedly save boxing or take it to the next level. It's going to take a cumulative effort from the promoters, their fighters, the managers and the publicists.

Scores of tickets -- thousands of them -- were given away for the Crawford-Madrimov show, and still the stands weren't full. Tickets were way overpriced and even when they were cut dramatically, it's not like there was a massive demand.

The business failure of Saturday's show in Los Angeles is just another example in a long list of failures to do the right thing.